From an early age, we learn to connect the name of an object with the written word that represents it. Young children are taught that “cat” refers to a small animal with fur and claws who likes to chase mice. Our world revolves around those connections between words and objects; we often even learn the written word before we are familiar with the object or concept itself.

Sometimes, though, we discover the unexpected. Do you remember being surprised by how a certain word is written: “Oh, that’s how you spell ‘pseudonym’”? Or learning for the first time that a phrase we use frequently in casual conversation, like “whatcha gonna do?” is actually a fast-paced, squished version of “what are you going to do?”

The process of giving spoken language a written form is challenging. Imagine a committee of English speakers trying to establish how to spell words like “thorough” or “knight” for the first time.

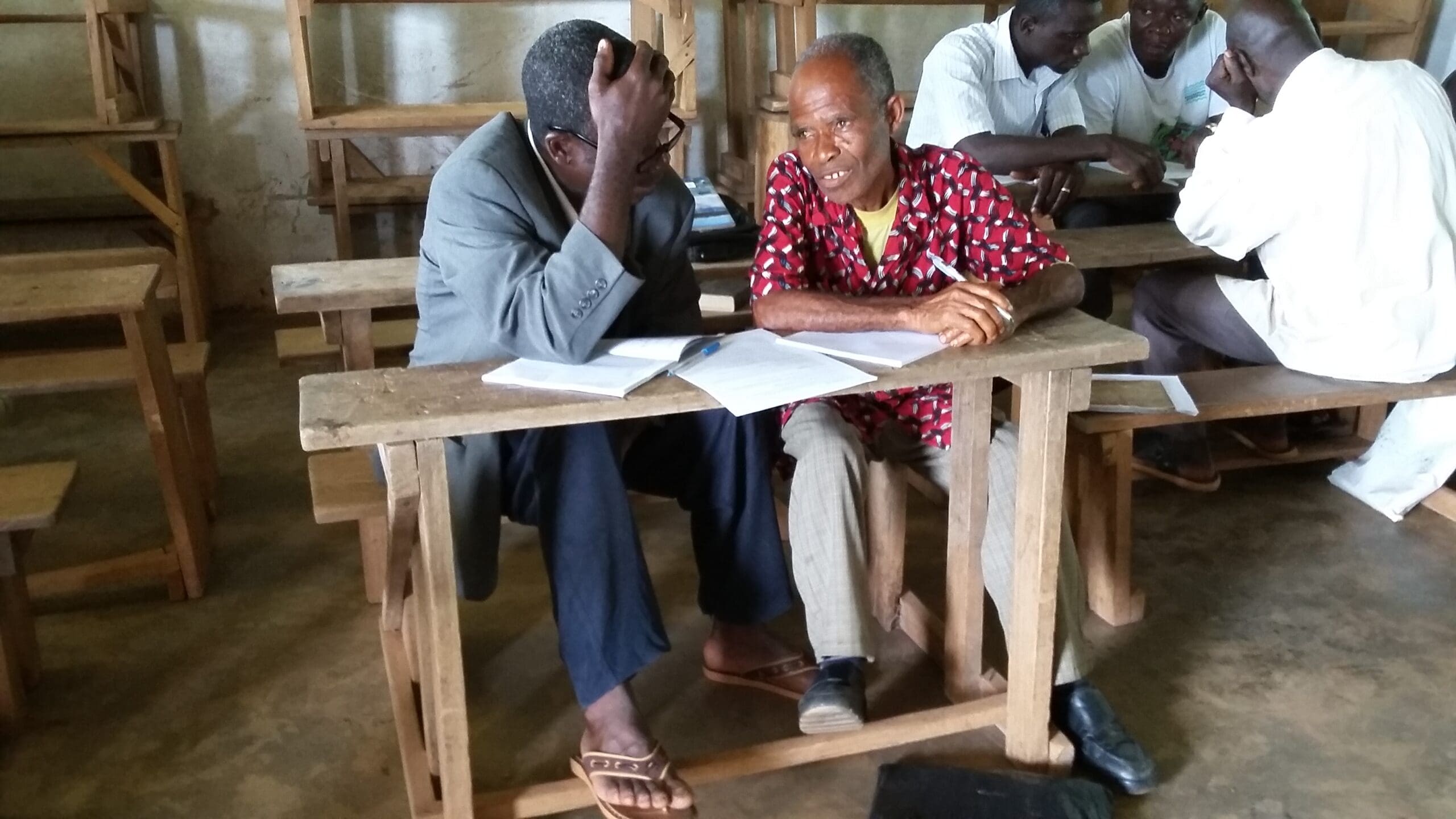

Consider, now, the people who have only known their language as a spoken language. They take shortcuts in their speech and blend their words together, too, just like we do. But when they first begin to put those words on paper, what will they come up with? Can they make the transition from how they pronounce the words on a daily basis to their original forms?

We think so. Not without difficulty, of course, and lots of discussion. Just imagine a committee of English speakers trying to establish how to spell words like “thorough” or “knight” for the first time. The process is hard and time-consuming, but the end result will be a written language where now only an oral form exists.

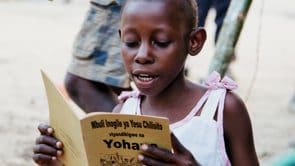

The written word has power — power to instruct a culture in the way of truth, and power to preserve the richness of a culture’s heritage. One of the oldest known civilizations, the ancient Egyptian civilization, left its legacy not only through still-enduring pyramids and mummies, but through the power of the written word in hieroglyphs, acknowledging thousands of years before Christ the immortality of writers:

Man dies, his body is dust,

his family all brought low to the earth;

But writing shall make him remembered,

alive in the mouths of any who read.

(Ancient Egyptian Literature, “The Wisdom of Amenemopet,”

translated by John L. Foster)

The weekend that I wrote this, a group of Kono speakers were working together to write portions of songs and stories from their language for the first time. Exercises like these, though familiar and simple to us, are paving the way for the most important words of all to be written: the words of God. And that’s why we’re here.

The grass withers

and the flowers fall,

but the Word of our God

stands forever.

(Isaiah 40:8 NIV)