One time I pierced my nose with a thorn. Actually someone else did — I just sat there as the thorn pushed steadily through my nose, my eyes closed peacefully, measuring my breaths, water seeping out of my eyes. It was blissful.

There is a pain deep in the bodies of my neighbors.

Magda doesn’t know where her husband is — he was conscripted two years ago and no one has heard from him since.

Bedo’s thirty-year-old son disappeared during the war. He returned a few years later — a shadow of who he was before.

Nira’s husband died of sickness days after her fourth child was born.

Hassan set fire to his house as he fled, destroying his family’s hard work rather than letting the coming army do so.

Mothers without babies, children without fathers, hunger and famine and sword.

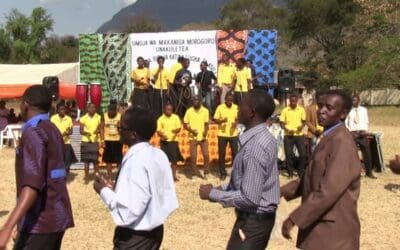

Yet there is a laughter deep in the bodies of my neighbors.

Magda greets me warmly and laughs as the haboba (grandmother) of the family sings a comedic song of welcome.

Bedo, his sight and hearing almost gone by now, chuckles as a child guides his hand to shake mine.

Nira smiles wide in response to the smile of her baby. She says to him, “Are you happy because Miriam came?”

Hassan slaps his friend on the back as they walk toward the market, and they erupt into laughter at a joke I’ll probably never understand.

They say we move to this country to help people. To change lives. To bring hope. Maybe it’s true? But here’s what this 26-year-old woman doesn’t bring: a lifetime of experience with suffering. A deep knowledge of keeping on because there is nothing else to do. Pain upon pain, heaped up, overflowing … and in the midst of that, laughter. I see these people enduring and finding joy, and my proud concept of myself is ground into the dirt. “We are a people of sabour,” they say. Of endurance. How much I have to learn.

This poem emerged as I wrestled with reality:

The royal women press food to my hand.

Generous, eyes smiling, teeth shining, voices rapid-fire.

Then they sit, silent — with.

They honor me, and I relax in their presence, homes, gazes.

They are the rich, and I am the poor.

What can I offer them? More than they’ve given me?

Never.

Not from myself.

I am beneath their feet.

My head is bare of the crowns they wear —

Jewels of suffering, refined in the fire.

Khata, the wife of one of the Mapa Bible translators, lost her nine-month-old baby. Healthy one day, cold and still a week later. Only a few months older than my own baby.

“I had a dream,” Khata tells me, “that her spirit was going up to our Father. So I talked to her that day, in the hospital. I said, ‘It’s ok for you to go now. You go, and I’ll see you later when I get there. Maybe tomorrow, maybe in a week, maybe in a month. You can go, baby.’ She died that day.”

I’m hit by my inexperience with suffering — my inability to speak into their realities.

And yet.

Can my Jesus offer something to these people? Khata thinks so. She and other Mapa believers now hold tightly to the hope of life after death.

I dare to hope with them.

No other god has descended into the immense suffering of the world. No other god has willingly joined the poorest of the poor, the sickest of the sick, and spread out his arms to receive them, to hurt with them, and to heal them.

I will always remember the thorn — the sharp and yet continuous pain of tethering myself to this place. I know that through it, beauty will come.

I feel this thorn pushing its way into my flesh, guided by the hand of a Mapa woman. I welcome the pain. In a few weeks the thorn will be replaced by a jewel, signaling that the wound has healed enough to hold something beautiful. But I will always remember the thorn — the sharp and yet continuous pain of tethering myself to this place. I welcome the pain. I know that through it, beauty will come. The crown of thorns that adorns the heads of my neighbors will adorn mine as well. And together we will see them transformed into crowns of righteousness. Together, we will taste salvation.

Come, Lord Jesus.